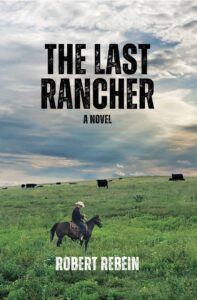

STAY TUNED FOR NEWS ON THE LAST RANCHER BOOK TOUR

Beginning June 2024

Readings and author visits in Indianapolis, St. Louis, and Kansas City. In Kansas: Leawood, Overland Park, Topeka, Lawrence, Wichita, Salina, Hays, Garden City, and of course Dodge City.

If you would like me to visit your library, book store, university campus, or book club, contact me at rrebein [@] iu.edu.

PAST EVENTS AND APPEARANCES

February 2018

Monday, February 19, 7:00 p.m.

Reading and book signing at Lawrence Public Library

Lawrence, Kansas

Wednesday, February 21, 6:30 p.m.

Reading and book signing at Kansas City Public Library (Plaza Branch)

Kansas City, Missouri

Thursday, February 22, 6:00 p.m.

Reading at Kansas Author Dinner

Marriott Hotel

Wichita, Kansas

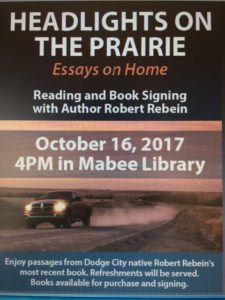

October 2017

Monday, October 16, 9:005 a.m.

Radio appearance on 1320 KLWN AM

Lawrence, Kansas

Monday, October 16, 4:00 pm.

Reading and book signing at Mabee Library

Washburn University

Topeka, Kansas

Tuesday, October 17, 7:00 p.m.

Reading and book signing

Skyline Room, MU

Emporia State University

Emporia, Kansas

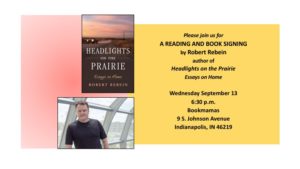

September 2017

Wednesday, September 13, 6:30 p.m.

Reading and signing at Bookmamas

9 S. Johnson Avenue

Indianapolis, Indiana

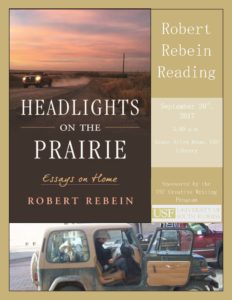

Wednesday, September 20, 3:00 p.m.

Campus visit at University of South Florida

Tampa, Florida

August 2017

Local Author Visits Dodge City Public Library

By Emily Garcia

August 9, 2017

Several hundreds of people have considered Dodge City home and a place to be proud of for well over a century.

Robert Rebein, who grew up in Dodge City, loves his hometown so much that he wrote a book about it.

Headlights on the Prairie was released on July 12, and since then has sparked up many interested locals.

“His book is about growing up in Dodge City and southwest Kansas. He grew up here in the 70′s and 80′s, and then he moved away,” said Dodge City Public Library director, Brandon Hines. “Each chapter is set up as a completely different, stand-alone essay. Some of them talk about Kansas in general. Others talk about rural Kansas. From the cover image of a pick-up kicking up dust on a dirt road in Hodgeman County to the final chapter sharing a personal conversation with his aging father at Manor of the Plains Senior Living Center, Headlights on the Prairie is the southwest Kansas experience for many who have lived or still live in the area.”

Rebein visited the DCPL on Friday for a book signing. According to Hines, Rebein was a definite crowd-pleaser.

“Judging by the laughter and the applause, everyone really seemed to appreciate having a local author come back,” said Hines. “There’s something about when you have a person who’s writing, or even just talking about a place where you’re very well connected to, it enhances the meaning I think.”

Rebein, who is related to David Rebein of Rebein Law Firm, is currently a professor of English as well as the chair of the English department at Indiana University-Purdue University in Indianapolis. He also wrote another book, titled Dragging Wyatt Earp.

“Dragging Wyatt Earp is described on Amazon.com as a ‘must-read for anyone interested in Western history, contemporary memoir, or the collision of Old and New West on the High Plains of Kansas,’” said Hines. “Both Dragging Wyatt Earp and Headlights on the Prairie are available for checkout at the Dodge City Public Library.”

According to Hines, Rebein’s book also mentions other issues and benefits of living in southwest Kansas.

“He also talked about health care being in southwest Kansas and having to drive to Wichita to see the doctor, and that was a big part of his experience,” said Hines. “He also talked about sports growing up and how big of an impact that is on many people’s lives in this area.”

Hines says that he enjoyed reading Headlights on the Prairie because of the personal connections he also holds with Dodge City.

“I grew up in the area, and I can really connect to a lot of those essays,” he said. “There were a lot of moments where it clicked and I was like ‘Oh, I remember that!’ or ‘I thought the same thing growing up.’ Additionally, there were also couple things he brought up that I forgot all about.”

To contact the writer of this story, email egarcia@dodgeglobe.com.

Upcoming events and readings:

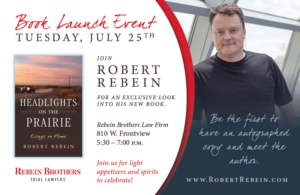

BOOK LAUNCH:

Tuesday, July 25, 5:30 p.m.

Rebein Brothers Law Firm

Dodge City, Kansas

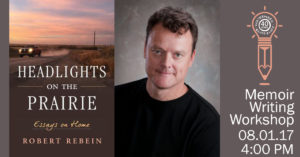

Tuesday August 1, 2017, 6:00 p.m.

Reading and book signing

Watermark Books

4701 E Douglas

Wichita, Kansas

Thursday August 3, 7:00 p.m.

Reading and book signing

Barnes & Noble Bookstore

Town Center Plaza

Leawood, Kansas

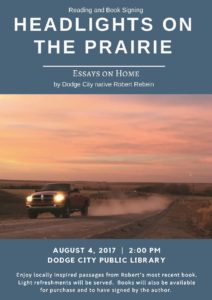

Friday August 4, 2:00 p.m.

Reading and book signing

Dodge City Public Library

Dodge City, Kansas

http://www.dcpl.info/?page_id=8883

Friday August 4,12 pm – 6 pm

Book signings at Dodge City Days Arts & Crafts Fair

Village Square Mall

Dodge City, Kansas

Saturday, August 5, 10 am – 6 pm

Book signings at Dodge City Days Arts & Crafts Fair

Village Square Mall

Dodge City, Kansas

Sunday, August 6, 12 pm – 6 pm

Book signings at Dodge City Days Arts & Crafts Fair

Village Square Mall

Dodge City, Kansas

July 2017

Headlights on the Prairie released July 12, 2017

See this site’s home page for more information. Also, be sure to follow updates and discussion on the book’s Facebook page, here.

June 2014

Dragging Wyatt Earp Named a Kansas Notable Book for 2014

The Kansas Notable Books List is the annual recognition of 15 outstanding titles by Kansas authors or about Kansas. It is the only honor for Kansas books by Kansans, highlighting our lively contemporary writing community and encouraging readers to enjoy some of the best writing of the authors among us.

A committee of Kansas Center for the Book (KCFB) Affiliates, Fellows, librarians and authors of previous Notable Books identifies these titles from among those published the previous year, and the State Librarian makes the selection for the final List. A reception and medal awards ceremony honor the books and their authors and illustrators.

Throughout the award year, KCFB promotes all the titles on that year’s List electronically, at literary events, and among librarians and booksellers.

See the full press release here.

Unsigned review in Notre Dame Review (Issue 37, Winter/Spring 2014)

Dragging Wyatt Earp is not well titled, given that one expects to find a growing up tale, its heart located in the teenage years. But it is much more than that. Rebein is writing more than memoir, though that genre, more or less, constitutes the structure of the book, and the memoir aspect is emphasized in the book’s first half. But the volume’s second half contains as much history, and not just of Dodge City, as it does memoir.

The book surprises because it is more than the sum of its parts. What is apparent throughout the essays is the fictional technique of presentation, of letting the writer describe, with a minimal amount of soul searching and analysis. Dragging Wyatt Earp mixes the staples of memoir, family upbringing, ambitions thwarted and achieved, along with some fascinating history of the country, done, mainly, in a documentary style. The book is about masculinity, plain work, the tensions and travails of domestic life. Rebein is not, in the contemporary mode, confessional. In many ways, he determinedly stays on the surface, letting the reader read between the lines, or wonder what the answer is to the human calculus he describes.

Read the full review here.

August 2013

Click here to watch a video of my reading at the Kansas City Public Library on August 4, 2013.

Get Back to Dodge

Author explores iconic town’s lifelong hold on his imagination

review in Kansas Alumni Magazine (August 2013)

by Steven Hill

The Dodge City of Robert Rebein’s youth was the kind of town where a boy too young for the pool halls and beer joints could buy a six-pack at the Kwik Shop and (fielding a genial “You be careful now, you hear?” from the cops he passed in the parking lot) jump in his car and cruise the town’s main street, Wyatt Earp Boulevard.

“Wyatt Earp, to us, was not a person but a place, a mile-long ribbon of asphalt that stretched from Boot Hill on the east to the Dodge House on the west, containing in that brief space all of our teeming and awkward adolescence, our collective longings and flirtations and our often ridiculous mistakes, few of which we had to pay for in any meaningful way,” Rebein writes in the title essay of Dragging Wyatt Earp: A Personal History of Dodge City.

The concept of “place” is key for Rebein, c’88, associate professor and chair of the English department at Indiana University Purdue University in Indianapolis. His first book, Hicks, Tribes, and Dirty Realists: American Fiction after Postmodernism, studies the role of place in contemporary American Fiction. Dragging Wyatt Earp forges a more personal course, mixing memoir, reportage, and a kind of hybrid nonfiction essay that combines researched history and autobiography.

“I think I became interested in the idea of place because I grew up in a place that had a very powerful and profound effect on me, without even really knowing it was happening,” Rebein says.

Not until he left Dodge City—a process he describes as “a series of widening circles” that started with attending KU and later took in graduate study and teaching in England, Tunisia and New York—did Rebein fully appreciate his hometown’s role in shaping him. He foresaw for himself a Hemingwayesque writing life chronicling his world travels and adventures. But when he sat down to write in some foreign outpost, it was always the Dodge City of his youth that found its way onto the page.

“I didn’t necessarily choose the material, but when I began to write, from the very first, that’s what I wrote about,” Rebein says. “I told myself, ‘Well, I still have to learn to be a writer, so I’ll use this material to learn, and when I’m good enough I’ll switch over to the real material.’ That’s how I felt when I was 25.”

Now 48, he returns again and again in these 14 pieces to his hometown and home state to plumb the question of what, exactly, is it that keeps drawing him back? Essays portray a somewhat chaotic family life. (The sixth of seven sons of Bill and Patricia Rebein, young Robby was as high-strung as a bird dog, “a hyperactive motor mouth prone to accidents and mischief of a more or less mindless sort,” a handful for his mother and the nuns at Sacred Heart Cathedral School.) His father’s salvage yard, where he was given free rein, “was my Harvard and my Yale,” Rebein writes, and it was full of colorful characters like Challo, an iconoclastic auto body man who forever set the standard for Rebein of the artist as renegade and rebel.

A middle-aged writer revisiting his own adolescence while exploring his hometown’s storied past might be expected to succumb to nostalgia. Rebein avoids the trap entirely. That’s a result of growing up, he says, in a part of the world that is in many ways a demanding place to live.

“The feeling you have when you’re there, and even after you leave, is a kind of radical ambivalence. It’s a feeling of understanding everything that’s so remarkable and beautiful and intense about the place but also everything that’s so demanding and difficult and far from perfect. It keeps you from falling back into nostalgia.”

Dragging Wyatt Earp is not an academic book; its strength lies in Rebein’s easy way of mixing personal tales and history. His portraits of western icons such as Custer, Coronado and Earp (less a gunfighter than a bouncer, in Rebein’s telling, who was more likely to use his gun for clubbing midnight drunks than for high-noon shootouts) are just as vivid as his portrayal of the colorful characters who prowled the salvage yard.

Neither is this engaging book solely about Dodge City. But Rebein’s essays suggest that not only can you go home again, in some ways you can never leave. Like a compass that stays anchored no matter how big an arc it draws, the Queen of the Cowtowns remains the rock-solid center of every one of those widening circles Robert Rebein has traced on his quest to get out of Dodge.

Just Passing Through Dodge City

by Brian Burnes

Robert Rebein really did get out of Dodge.

Reared in Dodge City, Kansas, Rebein writes in his memoir Dragging Wyatt Earp, that his birthright included the reality, acknowledged among his classmates, that hometown options were limited.

“Like the region’s cattle, wheat, and corn, we’d been raised for export,” he writes.

“We grew up with this knowledge that most of us were going to leave,” Rebein added recently. “Go to college, get a job somewhere. We understood. The teachers also understood it; there was a real sense of getting kids ready to go out in the world.”

Rebein’s later destinations included the University of Kansas, the University of Exeter in England, and Indiana University Purdue University in Indianapolis, where he directs the graduate English program.

The book’s title references the high school ritual of cruising the Dodge City boulevard named for the nineteen-century lawman. It suggests wry commentary on the juxtaposition of the frontier cowboy capital’s legacy and the more prosaic attractions of modern Dodge City. There’s some of that: Rebein describes his visit to the Boot Hill Casino and Resort, where employees portraying Marshal Matt Dillon and Miss Kitty greeted him.

But such anecdotes are trumped by the numbing tasks Rebein’s farmer-and-rancher father faced. One emergency—escaped cattle in a blizzard—prompted his father to take Rebein from his fifth-grade classroom and send him into the storm. The knowing look on his teacher’s face as she welcomed Rebein back days later represented a harbinger of rapidly approaching adulthood.

Rebein’s parents, who still live in Dodge City, are not disappointed that of their seven children all but two live elsewhere, including three in the Kansas City area.

“They raised us to be independent,” Rebein said.

Rebein speaks at 2 p.m. today at the Central Library, 14 W. 10th Street.

July 2013

Review in NUVO: Indy’s Alternative Voice

by Emma Faesi

Essayist Robert Rebein, who happens to live in Irvington, deconstructs his own past while telling the history of Dodge City, Kansas, in his new [book], Dragging Wyatt Earp. Dodge City used to be known for its lawlessness, loose women, and pleasure-seeking cowboys. Its Main Street was depicted in countless Westerns, serving as the face of the Wild West in its heyday. The city has changed, and now identifies better with grain elevators than saloons and six-shooters.

Rebein uses this shifting history as a mirror for his own. He intersperses memoir with tidbits of history about the city itself, debunking a few myths about some of its famous and infamous individuals along the way, including General Custer as well as Earp himself. The book is at its finest in its final section, which deals with a cowboy’s favorite subject: horses. Rebein’s writing shines when his subjects can trot, canter, and gallop. He unpacks his own and his family’s relationship to the equine, discusses the history of the horse itself and its uncanny bond to humans, and gives a candid account of his own attempts at cowboying after spending much of his adult life in air-conditioned universities.

The initial two-thirds of the [book] deal mostly with Rebein and his family, and are pleasant enough. Rebein’s writing is masculine and crisp, but takes its time to tell a story. As Rebein tells it, his upbringing had plenty of interesting quirks, but those quirks seem more appropriate topics for a family reunion than a [memoir]. If you’re looking for a memoir detailing the exciting life of a man who faced insurmountable odds, then keep looking. But if you’re seeking an honest tale about examining life in a changing American West, then you’ll find it in Rebein’s prose.

July 2013 Interview with Reason.com

Why Superman and Wyatt Earp Left Kansas But Still Loved the Place

Q&A with Robert Rebein, author of Dragging Wyatt Earp: A Personal History of Dodge City.

Nick Gillespie | July 18, 2013

In the hit movie Man of Steel, Superman, the last son of the planet Krypton, tells a U.S. Army general who questions his love of his adopted country, “I grew up in Kansas – you can’t get more American than that.”

And in many ways, you can’t get more Kansas than Dodge City, the legendary Wild West town whose main street is named after its most famous resident, Wyatt Earp.

Robert Rebein’s “personal history of Dodge City,” Dragging Wyatt Earp explores the deep history of the place (the Spanish conquistador Coronado scoured the area in the 1540s looking for the Seven Cities of Gold and George Custer got his first taste of defeat in the Indian wars in the 1860s while leading cavalry stationed in nearby Ft. Riley). But Rebein also evocatively reconstructs what it was like growing up in Dodge in the 1970s and ‘80s as the farming and ranching economy soured. The result is a riveting meditation not just on the Old West versus the New West but on how to treat the past with reverence while refusing to become trapped by it. For most of us, that’s easier said than done – and in the case of Dodge City, Kansas and many other isolated small towns still built on a 19th-century agricultural platform, it’s especially difficult.

But not impossible. By the start of the 2000s, writes Rebein, “Dodge City was again an open town….The population had grown by a third, most of it made up of young men come north from Texas and Mexico to work in the newly built [beef-]packing plants. Like the cowboys of old, they are mercurial and often well armed. Roughly a million cattle a year are slaughtered at Dodge City. The Roundup Rodeo, which headlines the annual Dodge City Days celebration has grown from a small, local affair to one of the richest on the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association circuit. It is as if the Old West, that brief period in the town’s storied past, has returned, big as life in the [21st century].”

The author of Hicks, Tribes, & Dirty Realists: American Fiction after Postmodernism (2001), Rebein is professor of English and creative writing at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis (IUPUI). This interview was conducted by Nick Gillespie and took place over e-mail.

Reason: Dragging Wyatt Earp is, as you note in your subtitle, “a personal history of Dodge City,” a town that exists only in myth for most Americans. This is the town where the Earp brothers and Bat Masterson earned their stripes as peacekeepers and Gunsmoke existed for 20 years. Dodge City’s entire appeal is grounded in its Wild West past. Yet you write, “A New West has come to Old Dodge City. I think with a laugh, Am I the only one who likes this one better?” Explain briefly the main difference you see between the Old and the New West, the old and the new Dodge City.

Robert Rebein: In the Old West, pretty much everyone, Indians aside, was from somewhere else—the Midwest, the East, a South ravaged by the Civil War, and so on. It was a place where people went to seek a second or third chance at life. In the New West, it’s different. You still have the newcomers, and they are still chasing that same old dream of a second or third chance, but you’ve also got this layer of people who were born and raised in the region and who think of themselves as “natives,” which is a curious term when you think about it in the context of the region’s history.

When I write that “a New West has come to Old Dodge City,” I am referring to this most recent wave of newcomers, most of whom are from Mexico and other parts of Central America, and the ways these newcomers are replicating patterns established in the Old West, where the whole idea was to get somewhere first and then make money off the people who came later. You know, Levi Strauss selling jeans to miners during the Gold Rush. Something very similar is happening in Dodge City even today. The people selling stuff to newly arrived immigrants today are the immigrants from 10 to 15 years ago, who have moved out of the beef-packing plants and have opened bars, restaurants, used car lots, and so on. I’m intrigued by this. I think it’s interesting and ironic on all sorts of levels.

Of course, in the Old West, the cowboy was revered and mythologized (even as he was relieved of his wages by gamblers and prostitutes), while the Mexican beef-plant worker is largely invisible, especially to those who live outside the region.

Reason: Among its several meanings, your book’s title evokes the pastime of bored teenagers with nothing to do but to drive up and down a town’s main drag in cars or bikes (Wyatt Earp Boulevard in this case). This is reminiscent of scenes from movies and novels such as American Graffiti, Dazed and Confused, and The Last Picture Show. Now that small towns are connected to everywhere else via the Internet and cable TV and home entertainment, does that sort of public boredom exist anymore? Your account of the late 1970s and 1980s may have been the last moment before the great cosmopolitanizing (for lack of a better word) of the country.

Rebein: I think if you asked the teenagers of Dodge City if they were bored, their immediate answer would be, “Hell, yes, we’re bored!” However, boredom takes different forms these days. One of the things I’ve come to realize by going places and reading from the book is that the 1950s and 1960s really were the Golden Age of “dragging Earp.” In many ways, the version my classmates and I took part in during the 1980s was a weak imitation of a ritual that even then was passing away, and for the most part kids today don’t “drag Earp” the way we did. On prom night, maybe, but not three nights a week all summer long the way we did.

But they’re still small-town kids at the end of the day, and their boredom still manifests itself in small-town, as opposed to suburban or big-city, ways. Dragging a keg out to a dried-up lake. Driving two hours each way to watch a football game. Working a couple of different part-time jobs during the summer because “there’s nothing better to do.”

I’m someone who loves the Internet, and I’m on it all the time whenever I’m in Dodge City visiting, but I would challenge the idea that it has somehow connected Dodge City to places like New York or Miami. I’d say the connection is theoretical, at best. It’s one thing to watch shows set in a big city, it’s another thing entirely to actually visit these places or, better yet, work up the nerve to move there. I say this even though leaving is something most Dodge City teens are still raised up to do. We have a saying there. You’ve got two choices: Grow roots or grow wings. Mostly Dodge City is in the wings-growing business.

Reason: You write that Dodge City has always been about commerce. Cattle and crops in the old days, as well as human flesh and booze. Spaniards wandering the area looking for gold. Farming, ranching – typically done under less than ideal circumstances. Talk a little bit about how the economic basis of the city – and of Kansas – informs the character of the place. And how (or whether) changes to the economy have changed that character.

Rebein: It’s funny. When most people think of Kansas, they think of it as being a middling place—middle America, salt of the earth, that sort of thing. But in reality it’s a land of extremes. Drought, 50 mile-an-hour winds, 117 degrees in July, 20 below zero in January, etc. That’s the reality of the place. It’s true that in between these extremes, you will encounter some spectacular weather—pure, bracing air, abundant sunshine. George Custer got a whiff of that and fell in love, but later he encountered the extremes as well.

Reason: Your memoir eschews trauma for depictions of work. Your old man was a farmer and a rancher and an auto-shop guy. Your mother worked outside the home despite having seven boys to feed, clothe, and look after. How does your family’s experience with long hours as a given reflect the values of the West? Or does it not really reflect anything larger than your family’s values?

Rebein: When I started writing the book, I asked myself, “Can you have a memoir about a happy childhood?” As you suggest, a lot of memoirs catalogue trauma, and even those that don’t deal in trauma sensationalize divorce, drug and alcohol abuse, mental illness, and so on. I’m not saying that the authors of these “misery memoirs” are lying about their experiences, because for the most part I don’t think they are. A lot of these childhoods really were terrible, and so when the authors who lived those lives sit down to write, that’s what they’ve got to deal with. That’s their material.

But in my case it’s different. I recognized early on that my childhood, when I looked back on it, offered a whole different menu of themes. My parents have been married for more than a half-century. For the most part, they’ve lived very intense, fulfilling lives. As a child, I got to be part of this big family in which independence was stressed and everyone worked and when we sat down at the dinner table everyone got to talk. There was none of this “Shut up and eat your food.”

It was fun. One of my brothers would tell a story about some movie he had just seen, and the rest of us would ask him questions about it, and that would lead to another brother telling a story about something that had happened to him that day and how he had responded, and then my parents would jump in and ask, in an almost detached, theoretical way, why he had responded that way and not this way. The basic idea we operated by was that the world was an interesting place and people were absolute freaks, you never knew what they might do, and to fail to note all this and learn from it was to fail to live your life to the fullest.

Of course, it wasn’t always easy. I remember times when my dad had millions out at the bank in loans and the weather was not cooperating and it looked like we might lose it all. As a very young kid, I got to see firsthand how he responded to that. I got to watch him and ask, “What’s he gonna do now? Is he gonna crack? Are we gonna make it through this rough patch?” I still think about those times. I still remember the things we did, things that were said. I remember once, a terrible situation, wheat harvest going badly, equipment broken down, storm rolling in. I was maybe 12 years old, beside myself with worry, and I asked my dad, “What are we gonna do?” And he just turned to me and gave me this weirdly calm look, almost laughing, and says, “We’re gonna try, that’s what. And if that doesn’t work, we’re gonna try harder. We’re gonna get up earlier and go to bed later.” And when he sees that I’m not buying any of this he just shrugs and gives me this crazy one-liner that I will never forget. “There are very few problemsin this life,” he says, “that cannot be fixed by getting up earlier in the morning.”

Now, you and I know that that’s bullshit on some level. If you’ve got paranoid schizophrenia, getting up earlier in the morning is not going to help you. Having said that, there’s no denying that having been exposed as a child to that attitude is a very powerful thing. One of the things I wanted to do in writing the book was to honor that kind of upbringing in an honest way, full of realism and devoid of nostalgia and sentimentality.

Was my childhood unique that way? I don’t think so. I think a lot of people, particularly in places like Dodge City, experience these things.

Reason: Kansas is routinely ranked as one of the best places to start a business. In 2012, it ranked 15th in CNBC’s list of business-friendly places and 13th on Forbes’ similar list. It’s affordable, has generally low taxes, good schools, and the like. Yet it ranks in the bottom half of the states for population growth. You yourself have moved out of the place and betray no strong interest in moving back. What explains the state’s inability to draw and keep people?

Rebein: If you want to understand Kansas you need to read a book by Timothy Egan called The Worst Hard Time. It’s about the Dust Bowl, and much of the book takes place in Kansas during a time when the state was cycling out of one of its recurrent boom phases and headed for the disaster of the 1930s.

The key to the book is dramatic irony. We all know what’s going to happen, but the people being depicted in the book do not. They’re getting rich on wheat, and then the price falls, and so what do they do? Plant more wheat. And then the price falls even farther, so they plant still more wheat. It’s a basic human response, but it’s chilling to follow when you know what’s coming. Then the rain stops and the wind starts blowing, and there’s nothing at all covering the ground, not a tree or a blade of grass, and it all starts blowing away. The people go broke. They pack up and leave. Towns that ballooned from 50 people to 5,000 in a decade witness the opposite trend, and most of those towns have not recovered even to this day. For town after town, the absolute zenith of population growth was 1929 or 1930.

There’s a lingering memory of all that, even today. While bigger towns like Overland Park, Wichita, and Lawrence, as well as the beefpacking towns farther west like Liberal, Garden City, and Dodge City, are thriving, the old farm-based towns have never matched what they were in 1929 or 1930, and the smart money says they never will.

I think a couple of lessons have come out of all this. The first lesson is that Kansas as a place is never going to be Texas or Colorado or Ohio. It’s too dry, too far from everything else, and the businesses that do best there—farming, ranching, energy exploration and production—do not require a lot of people. The other lesson is that if you do want to draw people and businesses to the state, you better try. You better understand that the lingering image of your state is a mix of the Dust Bowl, Superman, and The Wizard of Oz. If you want businesses to buy into you despite all that, you better put your best foot forward.

Reason: Fewer and fewer Americans are engaged in the actual cultivation and production of our food, whether vegetable or animal. According to the Farm Bureau, farm and ranch families comprise just 2 percent of U.S. households and only about 15 percent of the workforce is involved in growing, processing, or selling food. Is it a problem that we’ve moved away from direct involvement in the creating of the stuff we eat? Or, given the ardor required, is it cause for celebration?

Rebein: You won’t find much nostalgia for the “good old days” of farming and ranching in places like Dodge City. That’s more of a Midwest phenomenon. Take my father. He inherited half of 160 acres, including the house he grew up in. By the time he was [in his mid-40s], he had run that up to more than 4,000 acres. The man had seven sons, but he didn’t think any of us should be farmers. Why? Because it was hard, for one. But also I think he understood that we needed to find our own way in life, just as he had had to find his way. He didn’t like the idea of giving us that life or laying it all out before us. As a result, he’s the last of a breed—at least in our family.

Still, I think there’s a loss of sorts here. I’m not very interested in politics. What interests me is experience. And what I do find a little disturbing about America today is the way that so many people are so ignorant about really basic experiences like growing crops or slaughtering animals for food or fixing a car.

However, this lack of experience does not equate to a lack of opinions. In one of the essays in my book, “Feedlot Cowboy,” I spend a day in a big commercial feedyard where cattle are being fattened for slaughter. A feedlot is a really interesting place full of all kinds of interesting detail. To understand what’s going on there, you really do have to go there and experience it for yourself. Now that’s not something most people would want to do, and I understand that. What I don’t understand is how someone who has not done that can have so many opinions about things like animal welfare or environmental issues or illegal immigration from Mexico. All of those things are in play in a feedlot in ways that are not predictable or immediately apparent, but because of the way we live now, most people will never get that. They’ll still have their opinions about it all, of course, but those opinions will be based, at best, on arguments, not experience.

Reason: You end your book with an account of a trip to the Boot Hill Casino and Resort, a low-stakes gambling operation that seeks to trade on your hometown’s storied past. It’s a ridiculous place in most ways, though you treat the trip with a mixture of warm feelings and get-a-load-of-this disbelief. Is the casino a metaphor for a town, a state – a country? – whose primary sense of identity comes from the past and that seems incapable of moving fully into the future?

Rebein: The term is “Old West tourism,” and it’s been a part of Dodge City’s economic playbook almost from the beginning. It’s hilarious to witness, but it’s also a smart move in many ways.

If you look at a map, you’ll see that Dodge City is nowhere near a big city or an Interstate highway. To visit the place at all requires a decision of greater magnitude than a decision to visit, say, Chicago. If you’re a business person, you ask yourself, “Why would anyone drive more than a hundred miles to come here?” and the answer that comes to you is almost always some version of “To relive the legend of the West.” Given that reality, your next question will always be, “How can we get these people to (a) stay awhile, and (b) spend the maximum amount of money before they leave?” Gambling is a great answer to both of those questions, so it’s not surprising the town has decided to go in that direction.

What is surprising is the other moves the town has made. For example, inviting a semi-pro hockey team to play its home games in the town’s newly built Special Events Center. Hockey? In Dodge City? It’s a little crazy, when you think about it, but I guess there are limits to how far you can go with all the Old West stuff. At the end of the day, if you build a sports arena you’ve got to have a team, and if the only team going is a hockey team, I guess that’s what you’re going to have.

But you know, it’s things like that that keep the place fresh for me. Dodge City is very aware of its Old West past, but it’s got a present to worry about as well, and I kind of like that in seeking that present Dodge City is still capable of a surprise or two.

Nick Gillespie is the editor in chief of Reason.com and Reason TV and the co-author of The Declaration of Independents: How Libertarian Politics Can Fix What’s Wrong With America, just out in paperback.

May 2013

Review of Dragging Wyatt Earp

by Cheryl Unruh

“Returning home is like that. The future gets left behind, a piano dumped on a stark prairie. Suddenly you’re left with nothing but your life and the past. You have returned. Full circle. Everything else is just a blur.”

Those are the words of Robert Rebein in the prologue of his new memoir, “Dragging Wyatt Earp: A Personal History of Dodge City.” Rebein, who grew up in Dodge, is now an English professor in Indianapolis.

When an author writes “a piano dumped on a stark prairie” on the first page, I know I’m in for a great read. A few pages later Rebein describes the grain elevators in his hometown as “Big white pencils busily erasing the Old West of yore.”

Language and stories are two vital aspects of memoir. “Dragging Wyatt Earp” excels on both counts.

Rebein’s essays about growing up in Dodge City are simply the tales of everyday life. He connects well with the reader because he brings each scene to life with detail and description. He helps us recall experiences of our own.

In “House on Wheels,” the author describes his family life (he was the sixth of seven sons) and the evolution of their home which included one remodeling project after another. “And this, too, shall pass,” was his mother’s mantra.

The author tells of hanging out at his dad’s salvage yard during his early grade school years in the essay “In the Land of Crashed Cars and Junkyard Dogs.” He studied the characters employed there and observed a variety of temperaments. And he told of Challo, the body man, who found and completely restored a Schwinn bicycle for Rebein, so Rebein could fetch Challo’s lunch more quickly.

His father sold the salvage yard after a few years and returned to farming and ranching. When a blizzard kicked up one day, Rebein’s father showed up at his fifth grade classroom and took him out of school. “‘The cattle are out,’ the old man informed me as I climbed into the cab of his pickup.” In the parking lot of his grade school that day, Rebein’s father taught him how to drive the truck, a stick shift.

Rebein wrote, “The cattle were spread out across two counties, and getting them back to where they belonged was an arduous task involving much in the way of human and animal suffering.”

“My part was to guide a truck loaded with alfalfa between snow-filled ditches (hence the impromptu driving lesson), while my father and several of my brothers and cousins prodded the exhausted cattle from behind. It was terrible, grinding work.”

The author includes quite a bit of history of Dodge City and the region. He tells of the drunken cow town that Dodge City was once upon a time, and writes about Wyatt Earp, the town’s famous lawman. Rebein follows Coronado’s expedition, visits scenes of Cheyenne villages, learns how to ride a bronc, and spends a day as a feedlot cowboy.

With the title piece, Rebein reminds us of a familiar teenage activity – dragging Main. In Dodge City, however, it was Wyatt Earp Boulevard that was dragged.

“The epicenter of my teen years was the parking lot below Boot Hill Museum, a rectangle of concrete the size of a football field…” where high school kids leaned against cars and drank beer. A metal cage for empty cans was in the parking lot and “most weekends we possessed no higher ambition than to ‘fill the cage.’ This was the kind of thing that mattered to us, not Wyatt Earp, not history.”

He and his friends were killing time. Not killing time until midnight or until their next football game. “… we were leaving. And not just for a year or five years, but forever. Like the region’s cattle, wheat and corn, we’d been raised for export, and most of us had learned this fact about the time we learned that Santa Claus was a fiction.”

Rebein’s memoir gives us a chance to think about our own relationship with our own hometown, recall our own stories, our own dreams. The book helps us remember the things we treasured in our town, what we took away from that place, and what we left behind.

April 2013

‘Wyatt Earp’ author connects with readers

by Kathy Hanks

Kansas has a refreshing western voice in Robert Rebein.

From the start of his book “Dragging Wyatt Earp: A Personal History of Dodge City,” Rebein pulls readers in with his strong sense of place.

“Christmas Eve 1990. I’m in a car on my way west across Kansas, the heart of it all, the prairie-bound stomach of the country, headed for a white-framed farmhouse where I know one light still burns in the kitchen.”

I know that stretch of highway and the farmhouse where the light burns in the kitchen. As a reader, I am immediately hopping into the car, riding along with Rebein, flipping through the pages as he tells his story.

The book is a collection of creative nonfiction essays told in a voice that is fresh, topped by Rebein’s great eye for detail. The narrative carries the book through Rebein’s coming of age in a unique family where his dad, Bill Rebein, is a dreamer, managing a scrap yard, farming, and then becoming a cattle rancher.

“By then he’d bought a horse buggy from the Amish in Yoder, and liked to drive out through his acres behind the steady clip of a pacer,” Rebein writes.

He tells about the priests and nuns responsible for his education at Sacred Heart Cathedral School. English and spelling were his two worst subjects, though he went on to earn a Ph.D in English. He currently teaches creative writing and directs the graduate program in English at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis.

The reader rides along with Rebein through the changes and growth in his community, from the meatpacking plants that brought an influx of new workers north from Texas and Mexico, to Boot Hill Casino and Resort.

Reading Rebein, you can’t help but like him, especially in the essay “Wild Horse.” His wife, Alyssa, is injured after being thrown from a wild horse, and he struggles with guilt and missing her riding with him. He can be literary, but at the same time he is just another cowboy in the cattle chute.

I already knew Rebein was an interesting man, having met him four years ago in the press room at the Dodge City Roundup. Rodeo organizers gave Rebein free rein to explore behind the chutes as the professional rodeo performers readied themselves like pro-football players before a big game.

Back then, Rebein spoke of working on this book and how the title piece examines the multiple meanings of the name Wyatt Earp, which, in the context of his hometown, exists as both the historical lawman and as the main drag in a community on the High Plains.

Loving the topic isn’t good enough for the writer, he said. Rebein practices what he tells his students.

“They have to find the universal theme that everyone can connect to,” Rebein said. ”Even in a piece on rodeo, growing up in a small town, or herding cattle, you have to find something the reader can connect with even if, at first blush, they couldn’t care less about the topic.”

Even if you don’t have a heart for western Kansas, or never “dragged” Wyatt Earp, readers will find something to connect with in this book.

“Dragging Wyatt Earp: A Personal History of Dodge City,” by Robert Rebein, is published by Swallow Press Book, Ohio University Press.

The book will be available soon at Bluebird Books.

Josh Flynn interview in Punchnel’s

Remembering to Remember

by Josh Flynn

There is a moment in Robert Rebein’s new essay collection,Dragging Wyatt Earp, when he shares a small anecdote with his readers. It’s a Thanksgiving weekend during his childhood. One of his six brothers, away at college, returns to Dodge City, Kansas, with a friend who had no place to go for the holiday. The friend, expecting an easy weekend away from the pressures of school, instead finds himself helping renovate the Rebein family home—a task consisting of long hours and arduous labor. And when it gets dark, surely time to quit for the day, Rebein’s father brings out floodlights so work can continue. The Rebeins still laugh at the memory.

Hard work and family are the driving themes for the essays in the collection, which ranges from straightforward memoir to immersion journalism, all focusing on what it was like to grow up in Dodge City, a place known for Old West legacies and myths.

Dragging Wyatt Earp opens with an essay about Rebein’s ever-changing childhood home. His father would begin a home alteration project and, just as it neared completion, a new idea would spring up and he’d jump into the next phase of remodeling before completing the current project. “My dad’s nickname among his friends was 85 percent because he would get everything about 85 percent done and then he would launch into the next huge project,” Rebein said.

Rebein reflects on these moments with a smile. There’s a fondness for the ordeals he and his brothers experienced, and writers will easily see how his father’s approach to work influenced Rebein’s approach to writing and his determination to keep writing. For example, when Rebein’s research for the book grew flat, he dirtied his hands and went out to learn what he needed to know, be it riding a bronc during a rodeo or working as a pen rider in a feedlot.

But ultimately, no matter the myth he was investigating or the activity he was experiencing, his father was at the core of his search.

“The more I got into [the writing], the more I realized it was about witnessing the intensity of his work even in the face of so much of it coming up to nothing—or what felt like defeat to me. The real key moment of putting it all together was when I realized how much of my own life continued to be like that and what I had learned from working through it,” he said. “Sometimes when I’m talking to my students I’ll say ‘You have to come to terms with something: writing is a tremendously inefficient process.’ And then I’ll say, ‘No one would ever build a house the way we write.’ There’s as much tearing down as there is putting up. But of course that’s how my dad built the house I grew up in. It was constant change. I think that’s what I learned from him.”

Rebein, an associate professor of Creative Writing at IUPUI and the English department’s graduate program director, comes from a background of literary criticism and fiction writing. “Fiction writing is very much a world where change and the transformation of character and plot are what you are thinking about all the time,” he said. “When you are writing memoir you are very interested in transformation. One of Nietzsche’s most influential pieces was called ‘On Becoming’ and it focused on transformation, change, and how we become the person we are now. [When writing memoir], you constantly ask yourself, how did I become the person I am?”

Early in the process of writing the book, Rebein made a list of what he thought were the ten most important moments of his childhood, considering the before, during, and after of each moment. Those experiences make up a lot of the first half of the book: stories about his father’s salvage yard, attending Catholic school, and cruising up and down Wyatt Earp Boulevard as a teenager, or “dragging Wyatt Earp,” as it was called in Dodge City.

“There are moments in every life that are game changers, moments when, after it’s over, everything is different. For some people it’s a huge traumatic thing, for others the moments are more subtle than that, little epiphanies, small shifts in perception or outlook. When you think about it, our lives are made up of these moments. When we look back, we do not remember weeks or months or years, we remember moments, the big ones,” said Rebein.

Rebein divides the self into two aspects when writing memoir: the remembered self and the remembering self. The remembered self is who he was at the time of the memory—perhaps a child rummaging through his father’s salvage yard or a teenager acting as a guide for a group of drunken businessmen on a hunting trip.

The remembering self is where he stands now as the narrator. The remembering self knows the outcome of a situation. The remembering self sees the future spread out beyond the remembered self’s moment in time.

“In memoir you need both,” he said. “We don’t want an essay where the child character is unaware of everything and there’s no adult narrator who is leading us to the meaning of the piece. Because of my interest in theme and always wanting to know why I am writing about something—what is it all about? what does it mean?—I think I developed the remembering self early on—this voice that stays pretty much the same all the way through. What was fun for me in these pieces was trying to get back to and recreate this remembered self. When I wrote the book, I felt like there were many vivid memories which weren’t bad memories at all—many were good and intense memories. But I wanted to recreate on the page this child and what his life and world were like.”

There’s also the matter of selection. His essay “The Identity Factory” spans eight years of school. It moves through time from various school grades, focuses only on certain teachers, and makes no mention of classmates or friends. “There are thousands of moments I could recount if I sat around and talked about that school,” he said. “But because you have to be so selective I think you tend to gravitate towards the ones that cause or that illustrate something important.”

Rebein said that as a writer one must not only value memories but understand why moments are remembered. “It’s the search for the reason you remember something that helps you create not only the meaning but also the intensity of it for the reader,” he said. “That’s what readers of memoir want in addition to authenticity—meaning and the intensity of lived experience.”

Dodge City may be 800 miles away, but the lived experiences Rebein writes about echo many experiences people have in Indiana. The themes and values of family and hard work displayed in the book’s essays are generally shared all over the state. “It’s very similar,” Rebein says. “Dodge City is a very rural place. And Indianapolis is an urban place, but in Indianapolis I feel like I’m never more than ten minutes in a car from being in a small-town environment. Indiana is a state of small towns, really. And it’s a state full of towns that in a lot of ways aren’t that much different from the town I grew up in.”

If there is one thing that makes Dragging Wyatt Earp such an enjoyable read, it’s the fact that, for the most part, it’s a happy book. This isn’t a “misery memoir” documenting trauma or abuse. The essays present problems, but there is a happiness—an awe—in Rebein’s approach to his experiences. This is a writer who loved his childhood and wants to share it with readers.

“I had a pretty great childhood in a lot of ways,” he said. “I wasn’t pampered. I wasn’t spoiled. I got to do a lot of things that city kids would never get to do, like driving a semi at twelve or thirteen years old, riding motorcycles or horses whenever I felt like it. Growing up in my family was a lot of fun. It’s amazing for me to think of now, but my parents were under enormous financial pressure, millions of dollars in farm loans to pay off, and so on, the whole time I was growing up, and yet they never transferred any of that pressure to us kids.”

“My story isn’t about overcoming adversity at all,” he said. “It’s about living an ordinary life that in its details was very extraordinary and quite different from what most people experience growing up.”

March 2013

Review in The Weekly View, Indianapolis, Indiana, March 15, 2013

by Caroline Everett

Understandably, the mention of Dodge City conjures up visions of cowboys and tales of the Wild West, but in Robert Rebein’s memoir, Dragging Wyatt Earp: A Personal History of Dodge City, you learn much more about Dodge City, Kansas, and the author himself.

Rebein skillfully pairs amusing and poignant anecdotes from his life with enlightening stories about Dodge City and Kansas history. You discover fascinating facts about Custer and Coronado while enjoying the tales of home remodeling, car rebuilding, and “real” cowboys.

The Rebeins, especially Bill, Robert’s father, were DIY before DIY was cool. All items that could be salvaged were so they could be reworked and rebuilt into something amazing. While both witnessing and participating in these projects, Rebein and his six brothers learned not only a myriad of mechanical skills but many life lessons along the way. They knew to respect the effort of a job well done as well as to appreciate the artistry in seemingly menial occupations.

Naturally there were moments of play, hence the title, Dragging Wyatt Earp, which refers to cruising in your car on Wyatt Earp Boulevard, a road which ran from Boot Hill to the Dodge House. This was a way to see and be seen by your teenage peers and something some Indianapolis teenagers during the mid to late-1960s might recall doing at 10th Street and Emerson Avenue.

The added bonus to this great memoir is the section of family photos inserted right in the middle of the book. They make you smile from ear to ear and welcome you warmly into this wonderful life.

Robert Rebein will have his launch for Dragging Wyatt Earp: A Personal History of Dodge City on Friday March 22 at 6:00 p.m. at Bookmamas bookstore, 9 S. Johnson in Irvington.

January 2013

Front Page of the Dodge City Daily Globe January 10, 2013:

DODGE CITY NATIVE WRITES BOOK

by Julia Kazar

Dragging Wyatt Earp includes history, memory, and more.

Growing up on the family farm, Robert Rebein had no idea that his life was extraordinary, or that others would want to read about it. It was only after he grew up and went off to college in a ‘big city’ that it started to sink in.

“When I moved away, met new people and talked about our experiences and growing up, I started to realize how unique my childhood really was,” Rebein said in an interview with the Globe. “I realized that not everyone starts to drive themselves and their younger brothers to school when they’re 13. Things like that, that I thought were so normal, other people didn’t.”

Of course, the realization didn’t happen over night. It took time. Rebein lived in different countries, learned about and experienced different cultures, and met people from all kinds of backgrounds.

“When you’re growing up, you think everyone is having the same experiences as you,” Rebein said, “that everything is the same everywhere. It’s only when you grow up and move away that you begin to realize that’s not the case.”

Realizing the unique experiences he had, and how interested others were in hearing about them, is what inspired Rebein to write his new book, Dragging Wyatt Earp: A Personal History of Dodge City, which will be released in March.

Rebein describes the book as one part history, one part memoir and one part literary reportage, meaning he goes out and experiences something in Dodge City, and then reports on it.

“In one chapter I talk about my memories of driving up and down Wyatt Earp when I was in high school. It was just the thing to do back then,” Rebein said. “Then I put that against the history of the real Wyatt Earp.”

The literary reporting that Rebein does in the book includes riding a bull in the rodeo, working in a feedlot for a day and “bucking the tiger” at Boot Hill Casino and Resort.

“Even though the book is written in three different sections, it can be read continuously,” Rebein said. “It has a good flow and just makes sense.”

Since his book isn’t scheduled to be released until March, Rebein is still working out promotion details. But, he knows he’ll come to Dodge at least a few times, probably when it’s first released and during Dodge City Days to promote the book.

“I think people in Dodge will really enjoy this book,” Rebein said. “There’s a lot that they can relate to in it, and I think people will be excited about it.”

At the beginning of the writing process, Rebein gave a reading of the first chapter he wrote in Dodge. He said the reaction was very positive.

“People were upset that that’s all I had written,” he said. “They wanted the rest of the book to be finished.”

Here’s what Kirkus Reviews had to say about Dragging Wyatt Earp:

An affecting memoir of life in small-town Kansas.

Wyatt Earp’s old haunt is still haunted by him, or at least some version of him, the heroic lawmaker that brings in tourists. Rebein (Hicks, Tribes, and Dirty Realists: American Fiction after Postmodernism, 2001) will have none of that: His Earp is “the greatest bouncer the West ever knew,” a man skilled at rolling drunk cowboys and shaking down former Confederate soldiers. More than that, Earp lends his name to a strip of asphalt that runs through the heart of Dodge City, where drag racing and beer drinking formed the heart of Saturday night. Rebein’s upbringing was eccentric but not particularly hard, by his account. His father was the master of the add-on and the remodeling project, but was otherwise fairly normal, though with twists. The owner of scrap heaps and habitué of body shops and other places where metal was king, he had a penchant for accumulating junkyard dogs, “all of them troubled in some way, unmanageable by anyone but him.” For a young Rebein, the world of wrecked cars became a wonderland, and he writes lyrically of the things that turned up in them, from porn to lighters to photographs to ammunition. Elsewhere, he deconstructs aspects of small-town life on the Western plains, including the rodeo, which as a teenager he shunned as yet one more thing that spelled hick-dom but for which he has an older fellow’s appreciation, and the casino, which has become a mainstay of Dodge City—and even more of a draw than the legend of Wyatt Earp.

A well-crafted work, and an all-too-rare glimpse of daily life in rural America.

December 2012

My essay “A Fire on the Moon” was recently chosen as a Runner Up in the 2012 Hunger Mountain Creative Nonfiction Prize.

Here’s what the judges had to say:

“A Fire on the Moon” bursts right off the starting line with narrative verve and deep character insights which keep the reader entranced. That the writer is able to layer the how and why of stock car racing with a coming of age story is quite remarkable. We felt ourselves in the stands as the engines roared and we tasted the burnt track. The tension near the end–will the brother die in this fiery mess–is tautly rendered. Overall, great narrative control and nonfiction storytelling.

That’s from Anthony Swofford, author of Jarhead, and Christa Parravani, author of the forthcoming Her.

See the announcement here:

http://www.hungermtn.org/contest-news/

Creative writing professor is also tall in the saddle

by Kathy Hanks

The Hutchinson News

Anyone who hung around until the end of Friday night’s Ranch Rodeo at the fairgrounds in Leoti would have seen the exhibition ride.

Following a hailstorm that briefly held up the event, spooking the wild horses even more, Rob Rebein flew out of chute and stayed on the bucking horse for 6 seconds.

Though he didn’t make it to the whistle, it was a pretty good show for a first experience.

What made the ride unique is that the 46-year-old Rebein isn’t a cowboy by day, but an associate professor of English and creative writing at Indiana University Purdue University in Indianapolis.

Even though this was his first time competing in the saddle of a bucking bronc, the tall, lean man in the creased Wranglers is no city slicker.

Currently living in Indianapolis, the Kansas native has spent enough time in the saddles of broken horses to know his way around a pasture on one. His father, Bill Rebein, operates a cow-calf operation, called the Lazy R Ranch, about 14 miles northeast of Dodge City.

Visits to the ranch are important for Rob Rebein, his wife, Alyssa, and their two children, Ria, 11, and Jake, 8.

But this trip he made without the family so he could work on his latest book, Dragging Wyatt Earp. Rebein describes it as “a collection of essays that attempt to explore the concepts of place and identity through a juxtaposition of memoir with revisionist history.”

Rather literary for a dude who was seen hanging out behind the chutes at the Dodge City Roundup the past few nights.

While some of his work is highly researched and scholarly, including a book of literary criticism, Hicks, Tribes, & Dirty Realists, other works are memoir-based.

That’s when his writing becomes lively.

“I feel when I write what I love, the voice is there,” he said. “It’s me finding a theme in a way the reader can connect. To make it that way for the reader is where the work comes in.”

His current project inclues sharing personal experiences growing up in Dodge City. According to Rebein, the title piece examines the multiple meanings of the name Wyatt Earp, which in the context of his hometown exists as both a historical figure and as the main drag in a small town on the High Plains.

Loving his topic isn’t good enough, however. Rebein practices what he tells his students.

“They have to find the universal theme that everyone can connect to,” Rebein said. “Even in a piece on rodeo, growing up in a small town, or herding cattle, you have to find something the reader can connect with even if at first blush they could care less about the topic.”

During the Dodge City Roundup, rodeo organizers gave Rebein free rein to explore behind the chutes as the professional rodeo performers readied themselves like pro-football players before a big game.

It’s an athletic event, Wild West spectacle and big social event all rolled into one, Rebein noted.

Monday night he was getting one last ride in at his family’s ranch. Then he’d pack away the cowboy duds before heading east.

“When I come here, I live it to the fullest,” he said. “When I head back, it’s about my writing.”

khanks@hutchnews.com